Nostalgia is a perilous emotion. We all have comforts from the past that we want to preserve in our minds and hearts, but it’s very easy to turn that into an imagined utopia, a prelapsarian state that never existed, and put our energies and processes into a faux-restoration. At the very least, that’s reactionary, and it’s the emotional and philosophical (such as it is) basis of fascism.

Passive nostalgia is also dangerous. Look no further than our senior New York Senator Chuck Schumer, minority leader, who seems to think that some era of the past when moderate Democrats joined with moderate Republicans to maintain the status quo will return. Schumer was elected to the Senate in 2004, so there’s a puzzle as to what era he means; was it when George W. Bush was trying to privatize Social Security and John Kerrey’s patriotism was somehow being attacked exactly because he was a war hero? Was it 2008, when Schumer did everything he could to do absolutely nothing about raising the minimum wage and helping people through the Great Recession? Was it 2009, when racists went apeshit over there being a Black President, and The New York Times was asking Obama if he was a socialist? What I’m trying to say is that in changing times, nostalgia and clinging to the past makes you, by default, a reactionary.

Nostalgia is a problem in pop music. So much pop music is about that perfect moment that never was, and clinging to it. That’s compounded by who gets to sing this to us. Whatever Taylor Swift’s next album will be titled, it will be the same set of egocentric love songs, it will hit all the marks—whatever her personal politics, it will be like all her other albums, and set as reactionary against changing times. But then she’s rich, and as G.K. Chesterton pointed out, the rich have no stake in their own countries because they can go anywhere, while the poor actually have a stake, they have no other choice.

Superstars like Swift come from the kind of money and comfort that make it possible to even pursue a career in music, something that’s inaccessible to too many talented young people—especially non-white kids—who just happen to be born poor. Poor kids generally don’t get music instruction in schools or at home, and their talents remain hidden. Instead, the pop industry churns out homogenized, predictable music (for a brilliant parody of how this works, watch Letterkenny Season 12, Episode 2, “Sun Darts”), nostalgia for an imaginary time when things worked and there was never a dissonant note or a song about getting high (in 1928, Lemuel Turner recorded “Jake Bottle Blues,” and in 1932, Cab Calloway sang “Have You Ever Met That Funny Reefer Man”).

(I’m also writing this after Saturday Night Live announced, during their big 50th anniversary season, that racist country musician Morgan Wallen will be a musical guest—on a show that once booked Gil Scott-Heron, Ornette Coleman, and Sun Ra. If only Lorne Michaels would show some nostalgia for when his show was hip.)

I argue that the fundamental reason that there is so much virtuosity, imagination, and fire in jazz musicians who came of age up through the early 1970s is that until Ronald Reagan was elected America used to invest in its children, and high schools were often great and with great music programs and band directors who turned out generations of stellar musicians, simply because the kids got the chance to play and got turned on by music (for the story of how this happened in just one city, read Mark Stryker’s Jazz From Detroit).

Jazz musicians, as a whole, have always been poor. It’s tough to make a bespoke, abstract music within a mass, commercial culture that wants things easy to digest and disposable (and with the help of a media that mostly treats criticism as product reviews). So you better believe they have a stake, both in a music that they have to give up so much to make, and in the country that produced it.

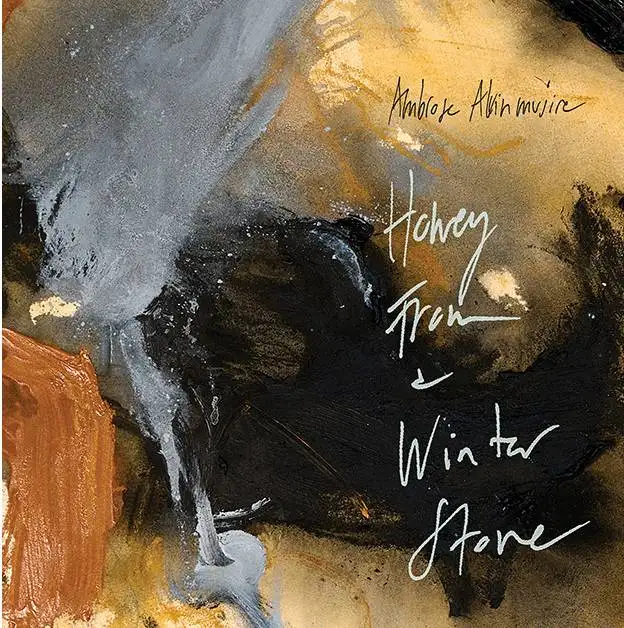

So we really should honor and acknowledge an aesthetic and social debt to musicians like trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, who released honey from a winter stone on Nonesuch Records in January. He’s a jazz musician—one of the leaders of the contemporary generation—and this is a jazz album, and it’s so enormously complex and mysterious and powerful that its existence is a blow against homogenization and reactionary nostalgia, and in 2025 that makes it one of the strongest possible political statements.

Not that there isn’t any nostalgia in the music, because there is. But rather than trying to pretend there was ever some perfection that never was, it’s the nostalgia for things and people that have been lost, nostalgia for thinking that life might ever be easy, especially for a Black person in America. Akinmusire himself says “This album is about the fears and struggles I personally face, as well as those many Black men endure: colorism, erasure, and the question of who gets to speak for my community, and why. There’s also the constant negotiation of what happens when I don’t conform to certain expectations or when I choose to reject those imposed on me. These are the complexities I navigate daily.”

None of this is explicit, even with the rapping and singing from the exceptional improvising vocalist Kokayi. He delivers snippets of thought, impressions, a stream of consciousness that expresses fury one instant and sweet beauty the next. You can’t pin him down, same for the music which ignores the expected formality of songs. Akinmusire uses the Mivos Quartet, a string quartet, and they wind through the album, spinning out a large scale structure. It’s important to point out this isn’t one of those exquisitely crafted, perfect ECM-type albums, there are actually moments that feel awkward and uncertain. But those are irrelevant because the music is constantly flowing from one state to another, passing through transitional phases, meandering like a stream before it expands into an intense trumpet solo of fiery vocalizing.

This is music that resist meaning as all the best music does. What is the meaning of Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata, or Steve Reich’s Drumming? Trying to discern that misses the point, the meaning of the music is in the effect it has on you, each time you listen to it. Does it stir something up? What is that thing? Is it the same as the last time? Can you even name it?

Sure, a song can do that, and in my life I’ve spent many hours with Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and Frank Sinatra narrating my own heartbreak back to me. But that was one thing, one feeling. What matters with honey from a winter stone is that the feelings are roiling, complex, rich. You can’t put a name on them, they can’t be pigeonholed, they are human in the best sense, in the way they honor the listener’s individuality. Taylor Swift will sing to you that she had a bad breakup, and you can think, yeah, I’ve had a bad breakup too. Akinmusire plays to you that he’s a man, and that he’s going to keep enduring and living his way, keep on keeping on, keep fighting the complexities that he navigates daily. And you can say, yeah, I’m going to keep fighting too.