The New York Public Library is really bringing it all back home with its small but stunning exhibit Becoming Bohemia: Greenwich Village, 1912-1923. The tightly curated show, open until February 1, fills two rooms on the first floor of the flagship location on Fifth Avenue. If you love the Village and its history, don’t miss it.

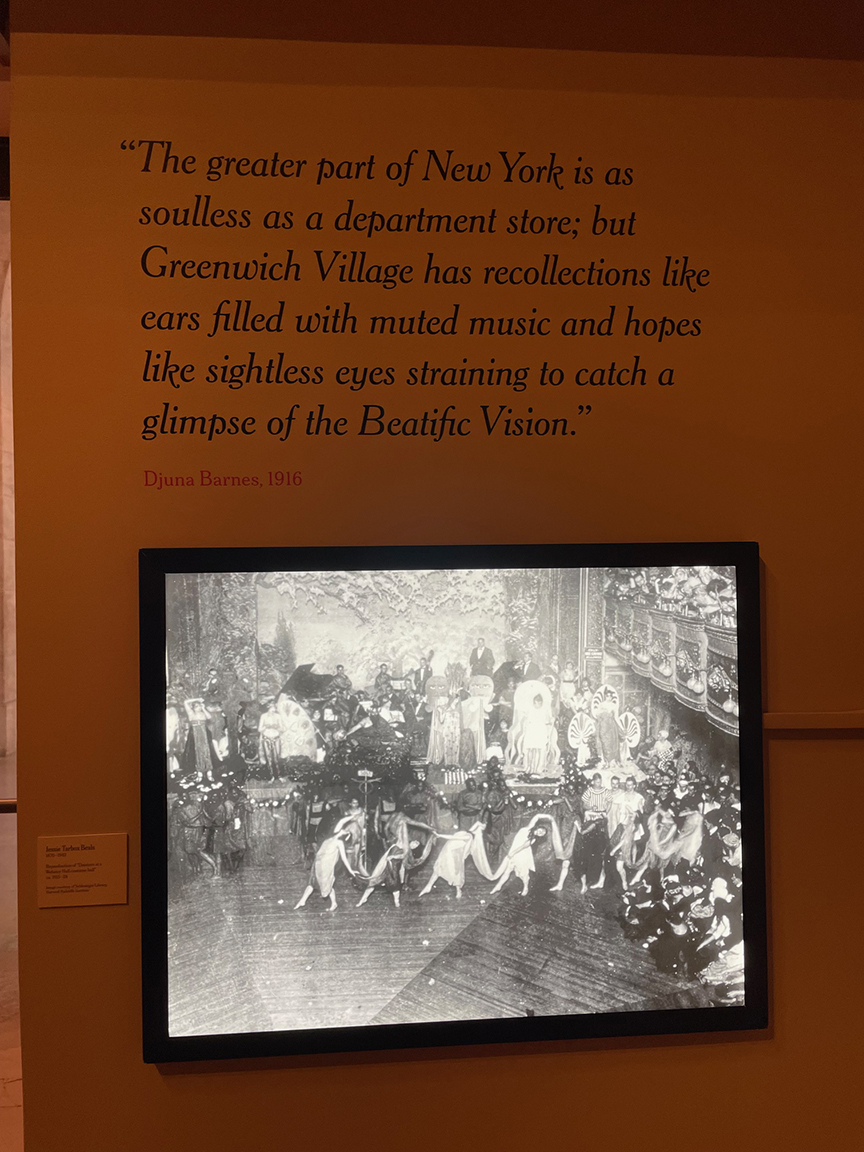

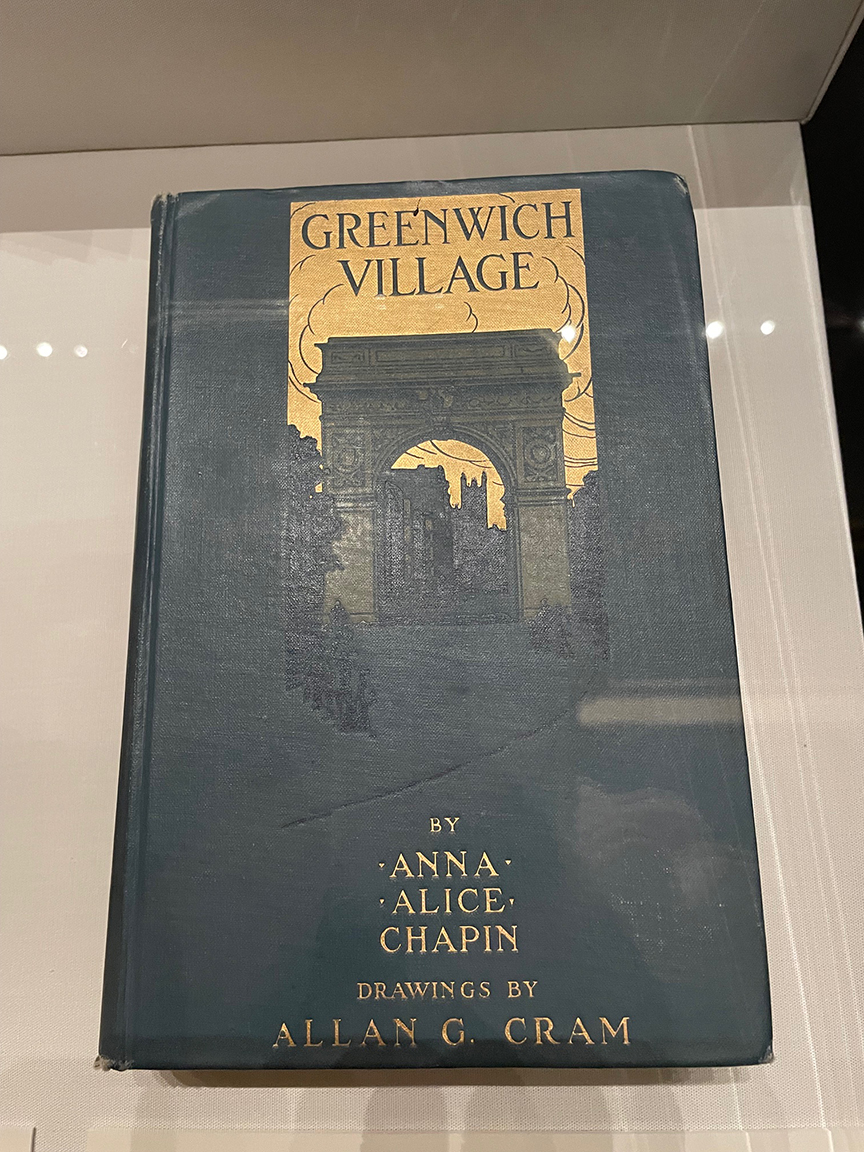

I’ve been a resident of the Village for five decades now (22 years in the East Village and 27 in the West Village). I’ve taken guided tours and read many books about the neighborhood, but I learned a lot. The combination of archival material from the library’s vast collections (books, magazines, drawings, photographs), along with the informative notes, brought this vibrant early period to life. I wanted to time travel back there.

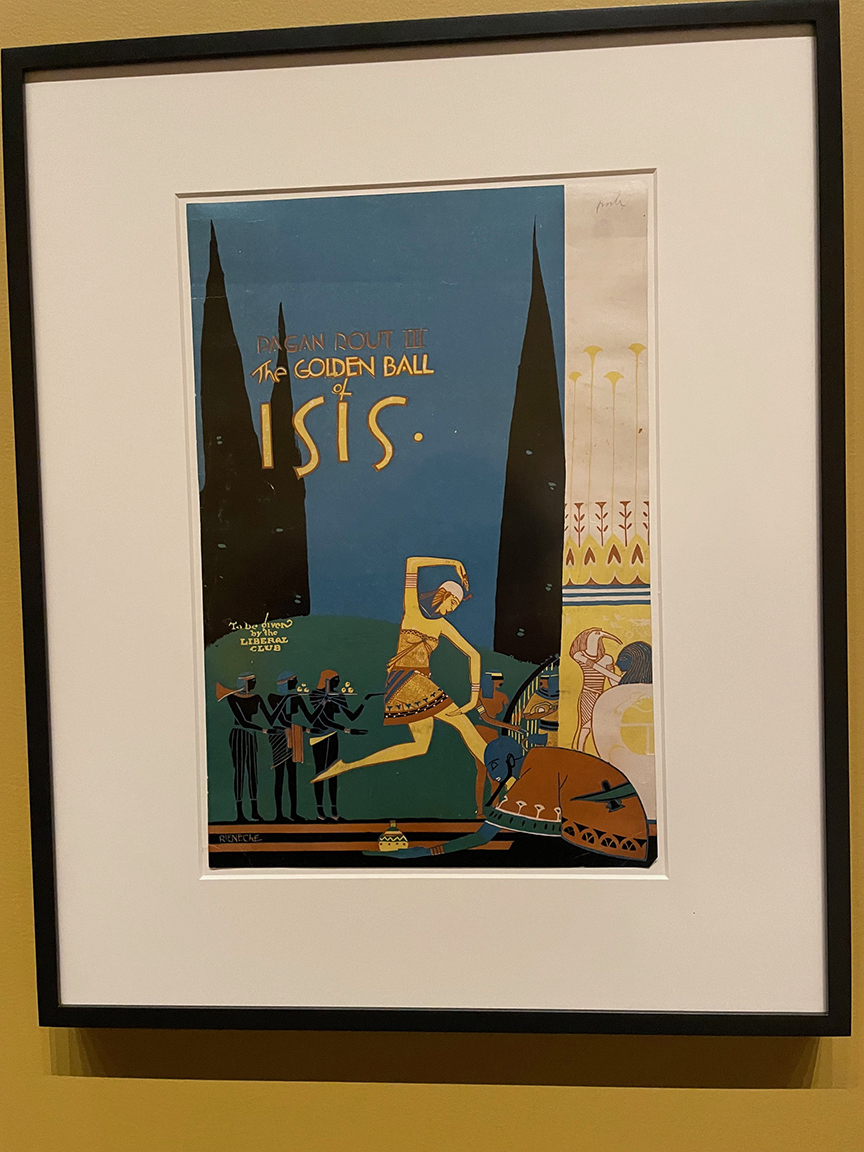

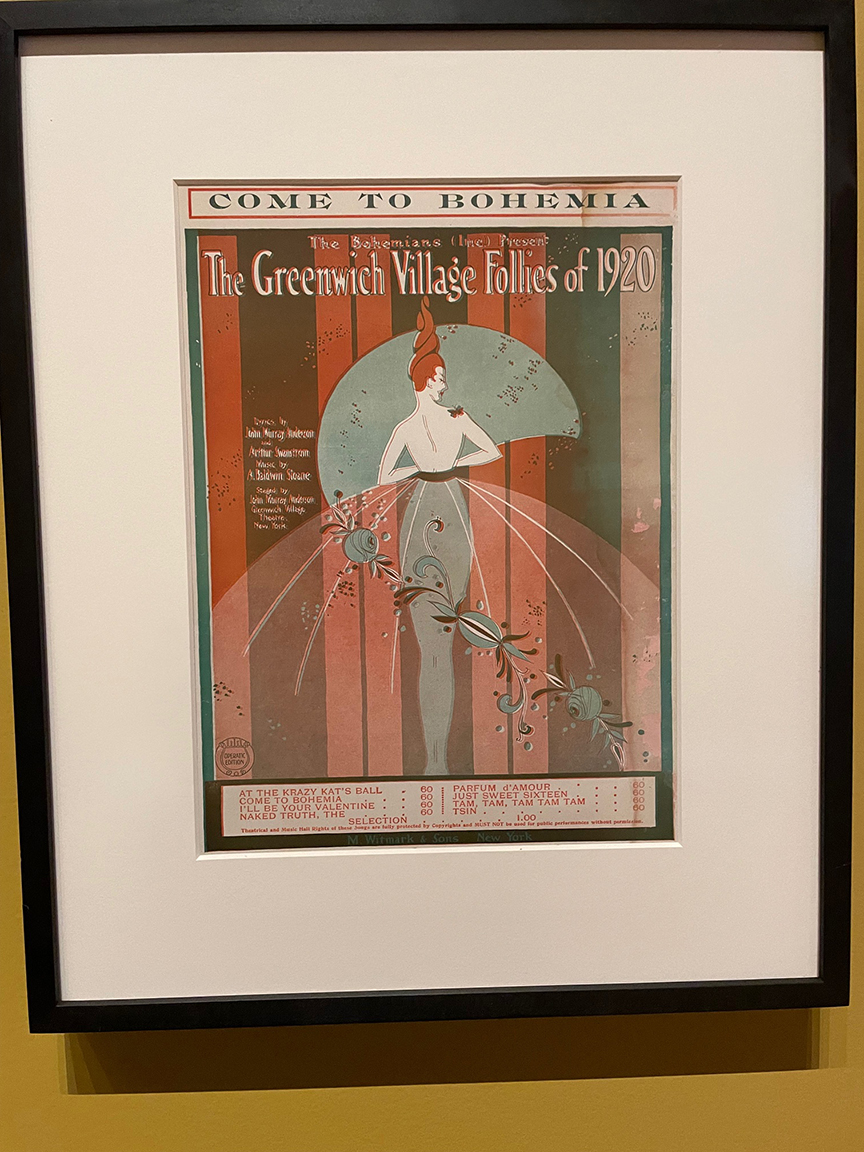

I’d be swinging from the rafters at Webster Hall at a costume ball. I’d drop by Polly’s restaurant to attend a secret meeting of Heterodoxy, a women’s club that promoted lesbianism and bisexuality. I’d hear Emma Goldman and Margaret Sanger talking up birth control. I’d see the latest Eugene O’Neill play at the Provincetown Players.

I’d spend the day shopping for bric-a-brac in Sheridan Square, relaxing in a tea house then going to a garret for a spaghetti supper. I’d hang out in Washington Square Park reading The Book of Repulsive Women by Djuna Barnes. I’d browse through the magazines at a bookstore on West 8th St. and look for the latest issue of “The Little Review.”

What an incredible time to be living in the Village. The women were bold and uninhibited. Clara Tice, known as the Queen of Greenwich Village, gained notoriety when the vice squad tried to confiscate her series of nude drawings on exhibit in a popular restaurant. This attempt at censorship boosted her career as an illustrator for mainstream publications.

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven created assemblage art from found objects and paraded around in a trash can bra and a bird cage necklace. According to the liner notes, “Her gender fluid, blatantly sexual public displays are seen as anticipating the feminist and performance arts movements of the mid 20th century.” (I could see her in the East Village lesbian theatre scene of the 1980s.)

Jessie Tarbox Beals, the first female photojournalist, lived in Greenwich Village from 1917-1920. Wealthy art patron Mable Dodge created her famous weekly salon to discuss the era’s radical ideas. She helped journalist John Reed organize the Paterson Strike Pageant, a large benefit held at Madison Square Garden to benefit the silk mill workers. (That poster jumped out at me, a native of Paterson, N.J. )

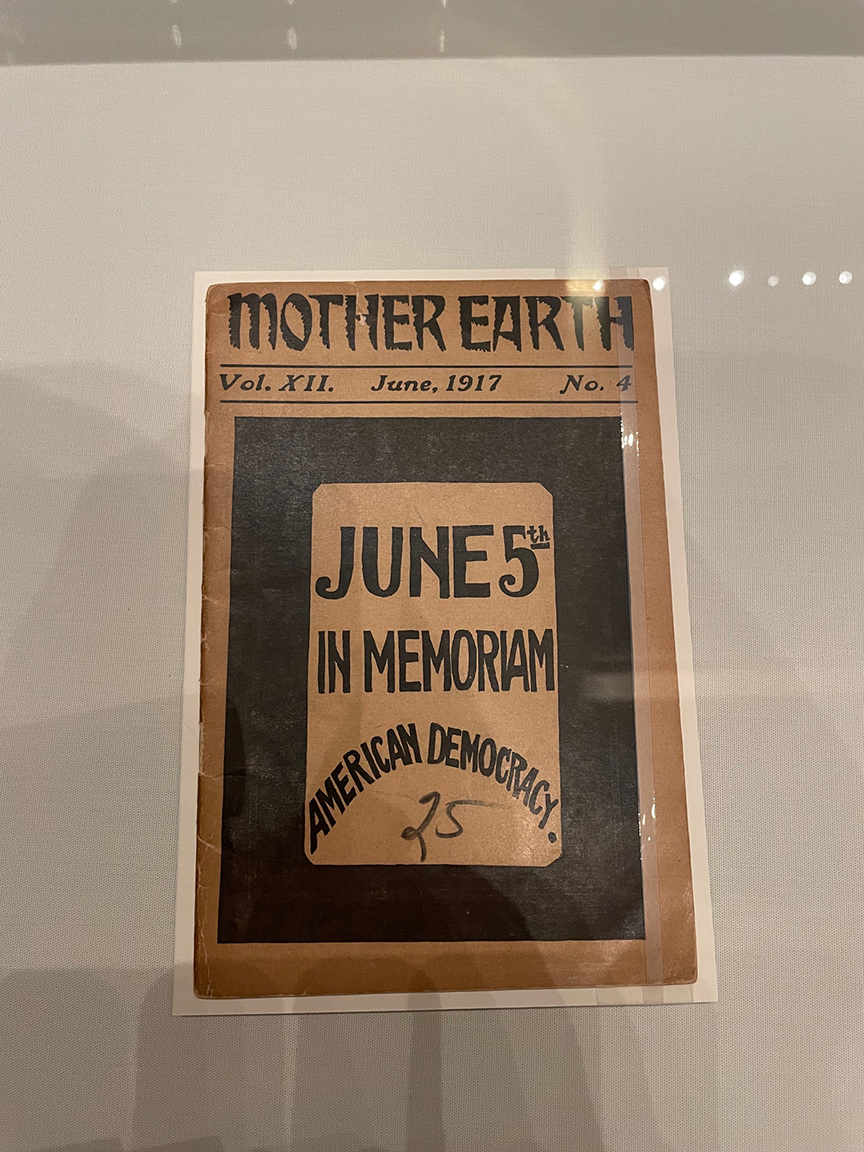

I got chills when I saw the 1918 cover of the anarchist journal “Mother Earth.”

The title stated “In Memoriam: American Democracy.” It felt like a scary omen from the past that rings true today.

These free spirits were attracted by cheap rents and the permissive vibes of the neighborhood. They exchanged work with restaurant owners for free meals.

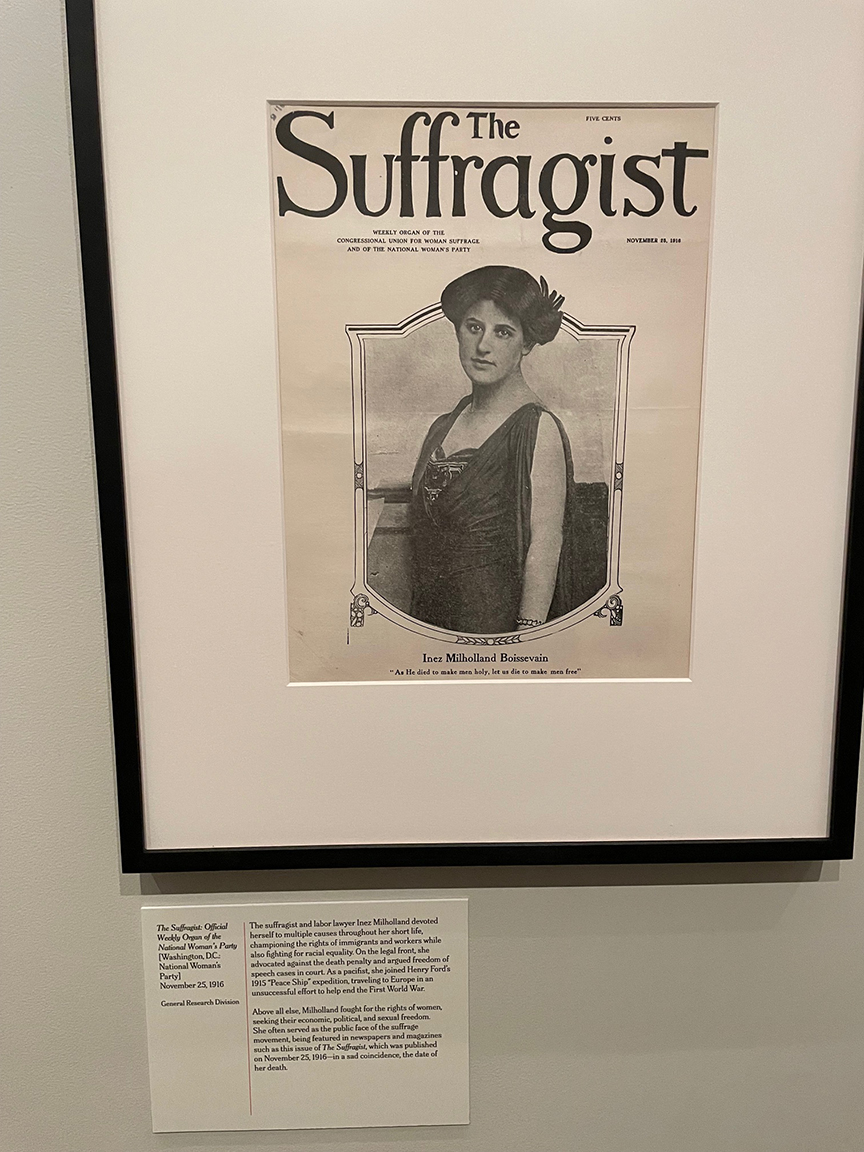

They came to make art, to be queer and to challenge the established social and political norms, advocating for many causes: women’s suffrage, gender equality, labor reform, socialism, anarchism, free speech, antimilitarism.

The literary scene featured an all-star line-up of poets: Hart Crane fled from Ohio as a gay teen to live an open life. (Some things never change.) Edna St Vincent Millay, (who was bisexual), arrived in 1917 and moved to Bedford Street. She became the first woman to win a Pulitzer prize.

Marianne Moore arrived in 1918 and became the editor of The Dial, an influential literary magazine. ee cummings arrived in 1916, later moving to Patchin Place. William Carlos William popped over from New Jersey.

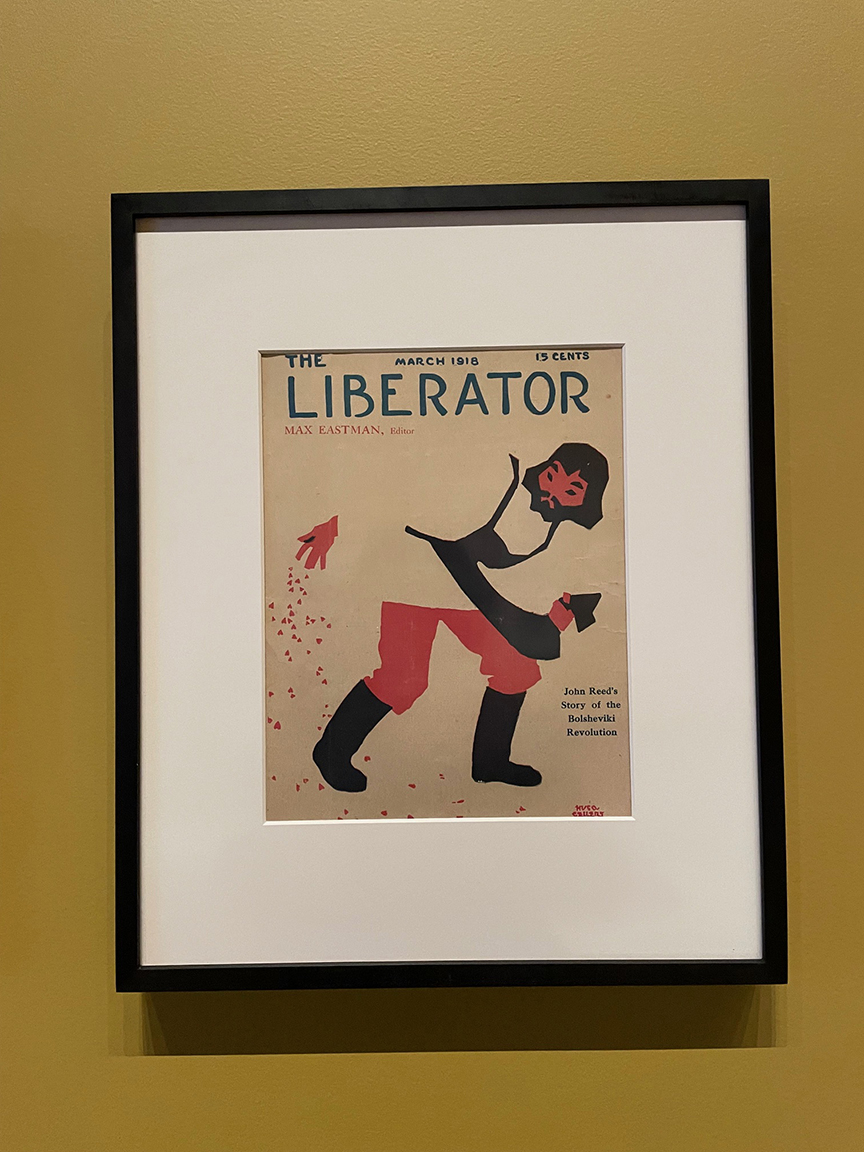

But despite the liberal politics of the residents, this environment was not very integrated. The Jamaican born poet, Claude McKay, worked as an editor for “The Liberator” and befriended prominent Village residents, yet the liner notes say, “He never felt entirely at home among the mostly white milieu of bohemia.” (Not surprisingly, the Harlem Renaissance overlapped with this time period).

The wild party started to wind down when the United States entered the World War in 1917 and our government had less tolerance for nonconformists. Also, the IRT extended its subway line downtown in 1918 bringing more curious outsiders.

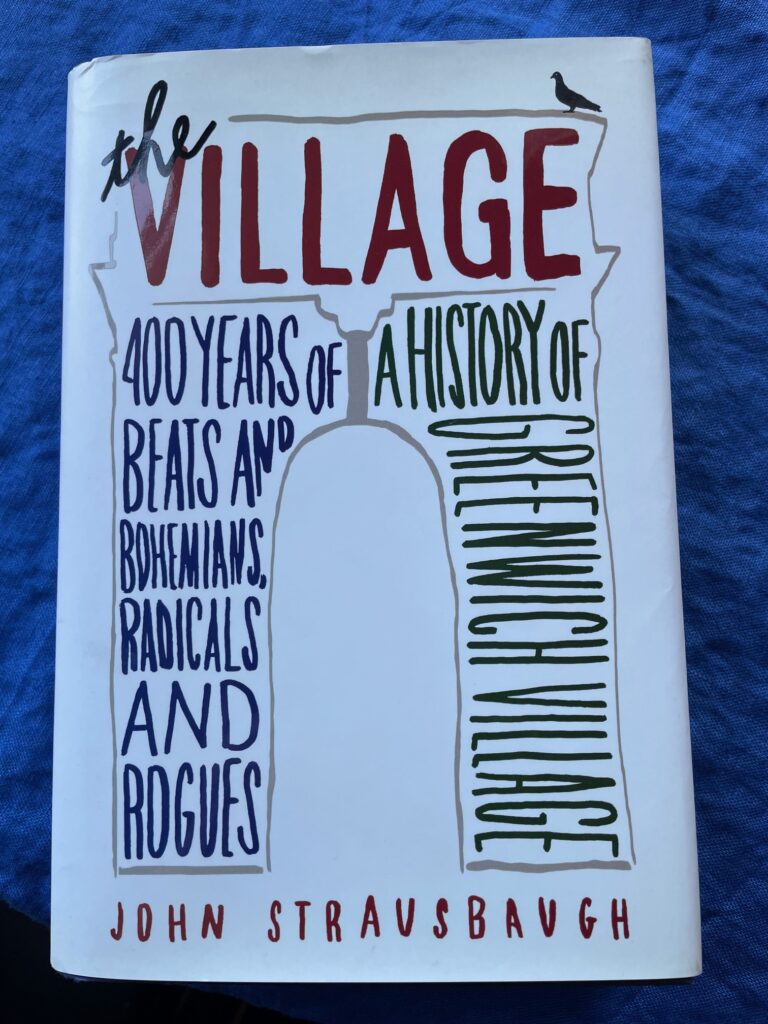

I loved this show but I was disappointed the NYPL book store did not have a big display table with related materials. I spotted one shelf with a few related books, including John Strausbaugh’s excellent tome The Village: 400 Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues: A History of Greenwich Village. (Full disclosure: John was my editor years ago and I’m quoted in his book).

After I left the library, I stepped out into the touristy Winter Village in Bryant Park.

I couldn’t wait to hop on the subway and get back to the Village. As I walked down West 12th Street and cut through Abingdon Square Park, I felt so grateful to live here. After the recent election, I think it’s time to repeat what the radicals declared in 1917 at the arch in Washington Square Park and once again proclaim Greenwich Village a “free and independent republic”.

Becoming Bohemia is at the Stephen A. Schwartzman Building of the NY Public Library, Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, and runs now through February 1, 2025.