“Baseball isn’t statistics,” legendary New York sports columnist Jimmy Cannon once wrote. “Baseball is DiMaggio rounding second.” I wonder if Tim Bassett, second baseman for Adler’s Paints, had that in mind when he quipped, decades later, “Is there anything more beautiful than the sun setting on a fat man stealing second base?”

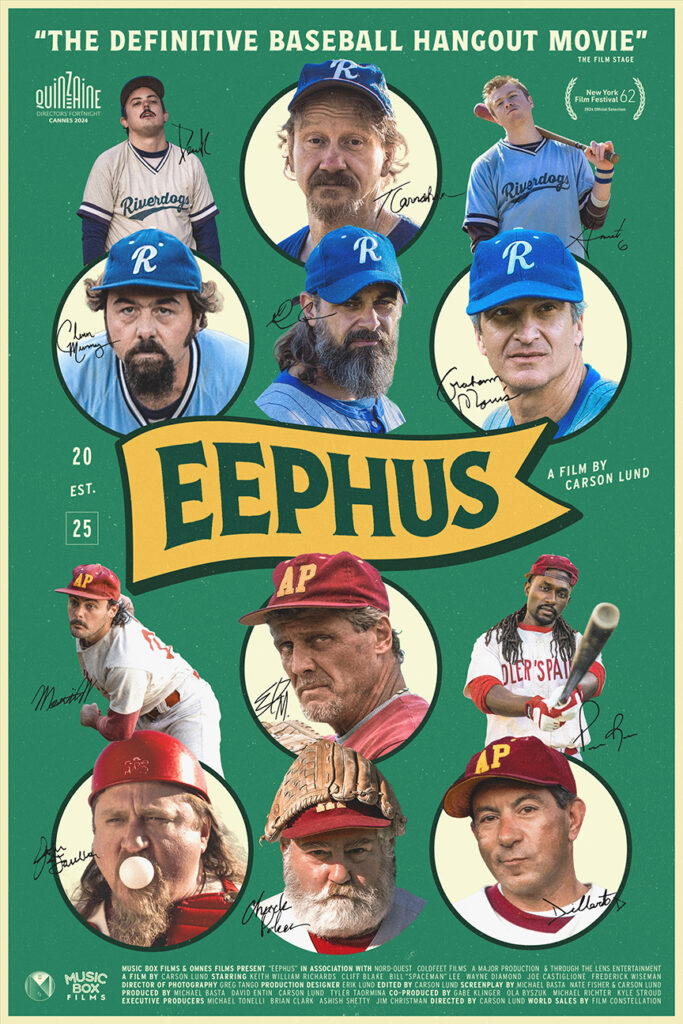

It’s entirely possible. Bassett, like his Adler’s teammates and their opponents, the Riverdogs, are creations of Carson Lund. The director believes in the primacy of the human element in baseball. He has been around the sport most of his life, and with friends Mike Basta and Nate Fisher he poured that experience into Eephus. A lyrical and elegiac baseball film opening March 7, it celebrates the languid pace and hang-out qualities of the game that have been lost in recent years.

Named after a rarely used arcing, slow-throw pitch, the film is set on a October day in 1994 as two rec league teams meet to play a make-up game — the last this field will see before it’s redeveloped. Some guys take it very seriously, and others are just out to have fun. Everyone knows it’s the end and mourns the loss of their ballpark, and the camaraderie they found there. But things take a turn for the absurd when the game goes into extended extra innings.

There are no stars or familiar faces in the cast, imbuing Eephus with a kind of authenticity rare for this kind of film. It also helps that it oozes a love for the game from every stitch and seam. The baseball is true — even if it’s a throwback version — but the film is never obtuse or exclusive. In fact, it’s eminently accessible. When it screened at the New York Film Festival last fall, a non-American viewer said through a heavy accent that she didn’t understand the game at all but enjoyed the movie. “That’s kind of the funny paradox of it,” Lund says. “It is deeply American in subject matter, and in its form and its visual language I think it’s a little closer to European sensibilities.”

Lund spoke with the Star-Revue about making a period baseball film, the origins of its title, and where Eephus fits in the baseball canon. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

“Eephus” is a great word, but it’s kind of an obscure baseball term. How did you settle on that for the title?

We wanted one of the characters in the film to be an eephus specialist and who would have an approach to the game that was singular and idiosyncratic. The eephus is such a rare pitch. It’s like an endangered species within the sport. We were trying to make a film that stands both within and outside of the baseball movie canon in its peculiarities and its sense of time and its rhythm, that sort of reorients your sense of time. And that’s what the eephus pitch does. It felt like an appropriate metaphor. It just also happened to be a word that we thought was very funny and sort of signaled a comedy. There were people who thought that we should maybe not name the film Eephus because even some baseball fans don’t know it. It was received as an out-of-left-field, oddball term that didn’t immediately scream baseball.

But for us, that was kind of the appeal of it — that it is this obscure, marginalized pitch within the game’s history.

You’ve said the film celebrates the more humanistic and experiential parts of baseball, rather than the data-driven, exotic-stats minutiae that so often takes up space in the conversation about the sport. The film is set in the 1990s. Could it have taken place now, or has something been lost in the game today compared to then?

The pitch clock has afflicted the game and taken it away from its roots as a game with its own sense of time with a lot of lulls and a lot of stasis. That’s where the drama of the sport arises, the sort of meditative Zen quality of it, and that’s what’s so interesting about it. That’s what’s produced so many fascinating characters and what made it America’s pastime. Adding a clock introduces a sort of urgency and kind of professionalizes it. It makes it feel like it can slot into our hyperspeed, late-capitalist environment. We can get the game over with, you can go back home, and you can go to work the next day and you’re not tired. It’s all about monetizing time, and I think that is just antithetical to what the game is.

Setting the film now wouldn’t have worked. We’re in a whole different era of thought and experience and socialization than we were in the ‘90s. That was a pre-technological age — we didn’t have phones to distract us.

I wanted to make this a movie about people who are really present in the moment. They care so much about this ritual they have once a week, it sort of distracts them from the rest of their lives, and they can occupy this little safe haven for those three hours or, in our case, much longer than that.

How much of the dialogue and characters come from your direct experience playing in rec leagues. There’s one line said by a spectator, that diners come and go, “but hot dogs will always be here and that’s a great thing.” It’s funny and weird and, in its way, authentic.

That line we just came up with. It just felt right. It felt true. I’ve played rec league for many years, and there are certain archetypes that appear again and again. Like people who join a team, whether or not they’re that person in their daily life, once they join that team they fill a role and perform in a way. As we were writing we were very aware of that. Neither of my two co-writers, my good friends Mike Basta and Nate Fisher, have a lot of experience playing baseball, but they have an interest in the game and have a similar sense of humor as I do.

We started very early on building the script with the top-down views of position players that you might see in a broadcast. We filled those little tiles with faces we found online that felt like they fit this particular archetype. What kind of guy is a first baseman? What kind of guy is a catcher? What kind of guy is a center fielder? We started from there and over the course of casting and rehearsing we found more specificity. I think it’s important to not lose sight of the fact that these guys are filling a role that they’ve probably have felt before. They’re modeling themselves after professional baseball players who have a certain charisma. The vernacular and lingo of baseball really informed the dialogue. Everyone’s communicating in these truisms and through the language of the game is kind of a way of avoiding talking about the impending collapse of this thing that they all love.

It’s all definitely rooted in my own observations over the years. I’ve taken notes at games that I’ve played — sometimes just mental notes. But I have to credit Mike and Nate. They understand the milieu and they would come up with stuff on the fly. And it felt right. Certainly the hot dog thing is — it’s just so absurd. I never heard someone say that, but I think it feels accurate — fixating on trivial details as being the truth of life. It’s a hot dog, you know?

Besides speaking to a simpler, more fun era of baseball, does Eephus have something to say about other baseball films? You can watch this and definitely pick up some Bull Durham, and Everybody Wants Some!! at least.

Not consciously. We really wanted to approach this with a clean slate, work from my own experience, and try to make it feel very true to that. But also, most of our reference points were not baseball films. They were films that were hangout movies about the end of something. So there’s Last Night at the Alamo, The Last Picture Show, A Prairie Home Companion — those all informed how we wrote this and structured it and centered this collective mood over any one protagonist.

I find that a lot of baseball films just feel kind of generalized and have never really, in my opinion, captured the rhythm and pace of the game. But no matter what, we can’t really get away from it. People on set would say this feels like the adult Sandlot. It wasn’t intended that way, but we all are bringing something to it and it’s all based on our own media consumption throughout our lives. So a lot of these allusions just happen naturally without us being conscious about it.

Do you have a favorite baseball film?

I love Bull Durham. It’s such a capital-M Movie, and the dialogue is so over the top. I think it’s really more of a film about sex and attraction and desire than it is about the game, but it still traffics in some of the lore and mythology of the game, and I know that director Ron Shelton was actually a player, so I credit him with that. There’s a real sense of understanding there. I like The Bingo Long Travelling All-Stars & Motor Kings for its location photography and humor. And then there’s one called American Dreams: Lost and Found by James Benning. It’s an avant-garde film. There’s no baseball happening in it. But it’s a series of baseball cards on screen as a sort of narration happens with contemporaneous events leading up to Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record. It’s like multiple streams of information happening at once; it’s fascinating. Benning was a baseball player, too, so there’s a real deep, deep understanding of the game, even though it’s very much a non-traditional narrative.

This last question is a curveball, but you’re a founding member of the filmmaking collective Omnes Films. There are a lot of people interested in this idea of working with others outside of legacy systems, be it in film or media or some other field, to build their own means of creating. What advice would you give someone who’s considering going down that path?

Don’t wait for permission. Just start doing it. Start building that family, start working towards the project goal. I found that as more people come on and the momentum builds, what needs to happen starts to happen. You find the resources you need. I think it’s just about doing and not waiting. There’s so much waiting that happens in filmmaking, and the goal is to try to minimize that. Use your friends as a strength. Just start going. It sounds a little general and vague, but that is the move.

Eephus opens March 7 at Film at Lincoln Center’s Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center, 144 W. 65th Street, with director Carson Lund appearing for Q&As March 8–9. Visit filmlinc.org for more information and show