If nations were born with original sin, America’s would be slavery. When Thomas Jefferson penned our Declaration of Independence from Great Britain, declaring it “self-evident” that “all men are created equal,” he was, like George Washington and other founders, a slave owner.

Indeed, during the Revolutionary War, while American revolutionaries waxed eloquent about freedom from kings and tyrants, it was the British that offered enslaved African-American men freedom in return for military service.

Slavery was integral to the colonies, northern as well as southern. Slaves literally built the wall of Wall Street. At the eastern end of Wall Street was the slave market, founded in 1711.

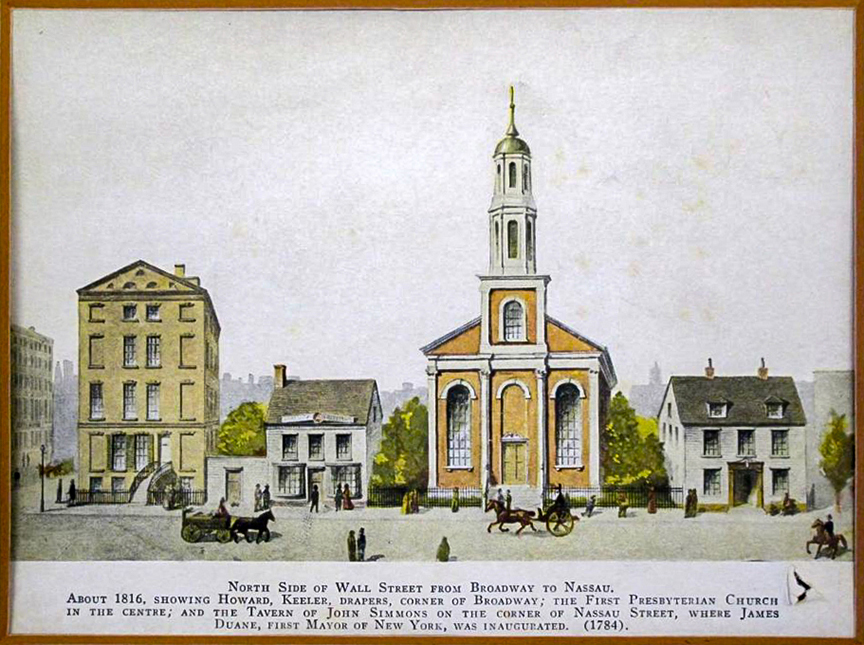

And at the western end, founded in 1719, was the First Presbyterian Church. It eventually became known as the “Church of Patriots” because so many of its leaders fought in the Revolutionary War.

Today, the First Presbyterian Church—which moved uptown to its familiar Village location on Fifth Avenue by 12th Street in 1844–is continuing to reckon with its legacy of slavery.

In February, in honor of Black History Month, the church co-hosted a public presentation on its research report, Old First and Slavery, which delved into slave ownership by early church leadership, and sought to research the church’s financial ties to the slave trade.

Slavery was once ubiquitous in New York City, which had more slaves than any other city in North America—and as high a percentage of slave owners (42 percent) as Charleston, South Carolina.

As report researcher Susan Jackson told the audience, given that the number of slave owners in the city was “shockingly large” and the church’s leadership were “a fairly wealthy group,” it is “depressing” but not surprising that many early church leaders owned slaves—including seven of the first nine pastors, and most of the trustees and elders during the turn of the 19th century.

The report offers some wrenching details, a window on an era when owning other humans was a mark of prosperity. Among its findings:

- After the “New York Conspiracy of 1741,” when multiple fires were set in the city and blamed on a slave rebellion, more than one hundred fifty enslaved persons and twenty Whites were arrested, tried, and convicted with many brutal executions. Old First trustee William Smith Sr. was a prosecutor in the trials. Quinimo, an enslaved person of Old First pastor Rev. Ebenezer Pemberton, was tried, convicted as a conspirator, and sold to a forced labor camp in the West Indies.

- Among the trustees who owned slaves were prominent, wealthy city merchants whose wealth came directly from slavery. They included: Peter Van Brugh Livingston, a founder of Princeton University; Alexander McDougal, organizer of the Sons of Liberty; and Robert Lenox, among the city’s richest men. During severe financial challenges suffered by Old First, affluent slave owners often used their own slave-derived wealth to cover shortfalls, provide loans, and fund construction.

- When the financial condition of Old First was weak, clergy salaries were reduced. In 1759, one pastor, Rev. David Bostwick, reported his salary was so inadequate he was required to sell two enslaved persons to support his family.

- Church records document more than 84 Black members, many just by first name, some of whom were acknowledged as free. Many left Old First to form their own church.

- Several slave-owning Old First church leaders were leaders in the New York Manumission Society, dedicated to educating, and gradually freeing, slaves. Slave-owning Rev. Samuel Miller gave a famous impassioned speech to Society in 1797, emphasizing that “ALL MEN ARE BORN FREE AND EQUAL” and characterizing slavery as “humiliating” in this “free country.” He at first advocated “emancipation in a gradual manner, which will at the same time, provide for the intellectual and moral cultivation of slaves, that they may be prepared to exercise the rights, and discharge the duty of citizens.” Later, by 1823, Miller had backtracked, claiming enslaved people “could never be trusted as faithful citizens….[They] must be colonized. In other words, they must be severed from the white population, and sent to some distant part of the world.”

Last month’s presentation is available on the YouTube page of Village Preservation, which co-sponsored the event along with the church and the Merchants’ House Museum. The report itself, completed in 2022, is on the church’s website.

As church member Ann Timmons put it, the report is “informative,” not a call to action, and the response by the congregation has been subdued. Relatively few read the report, which she described to the Star-Revue as “an invitation to a conversation” that in many cases had “not yet [been] opened.”

So Timmons, a playwright and a member of the church’s Facing Racism Action Group, penned a one-act play, wrestling with the report’s contents and the larger questions of slavery’s role in our history and institutions.

Her play, In Good Conscience, or The Manumissionist, was performed before a congregation audience in October. Focusing on Rev. John Rodgers and Rev. Samuel Miller, two slave-owning pastors who were leaders of the New York Manumission Society, it explores how they could possibly condemn slavery while themselves owning slaves and relying on church donations tied to slave labor.

Rodgers and Miller apparently believed that engaging enslaved persons in domestic service, rather than plantation labor, and looking out for their welfare, mitigated against what they acknowledged as the evil of slavery. The Society founded the African Free School in 1787, teaching enslaved and free Blacks reading, writing, arithmetic and geography and preparing them for citizenship.

Looking to spur additional conversations, Timmons hopes to encourage additional productions of her play. She can be reached via her website, www.anntimmons.com.

Excellent, and terribly upsetting, article. Thank you.