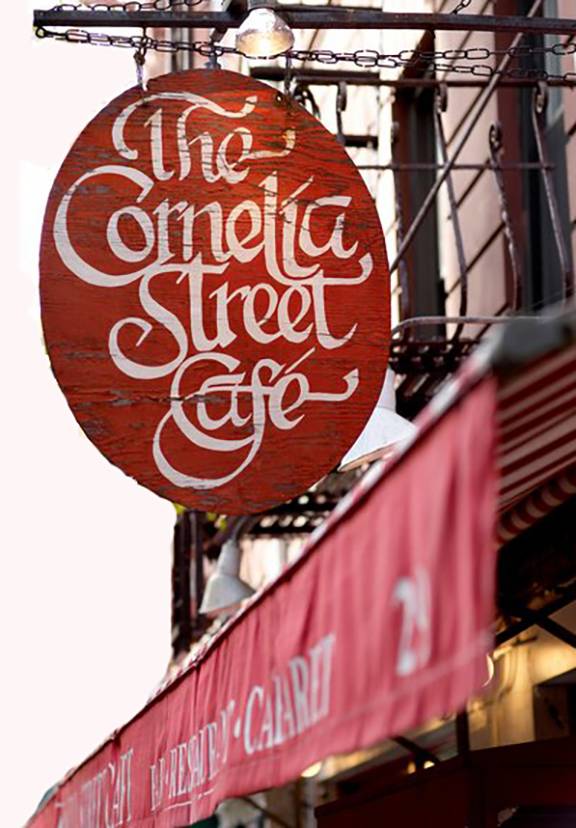

When the Cornelia Street Café announced its closure in 2018 after more than 41 years of operation — due to a crushing rent increase — the loss was acutely felt by the neighborhood and the community of artists who called the café basement stage home. For co-founder and owner Robin Hirsch, though, losing the place was a violent act that left a gaping wound, an experience he compared to what his parents experienced fleeing the Nazis in Berlin.

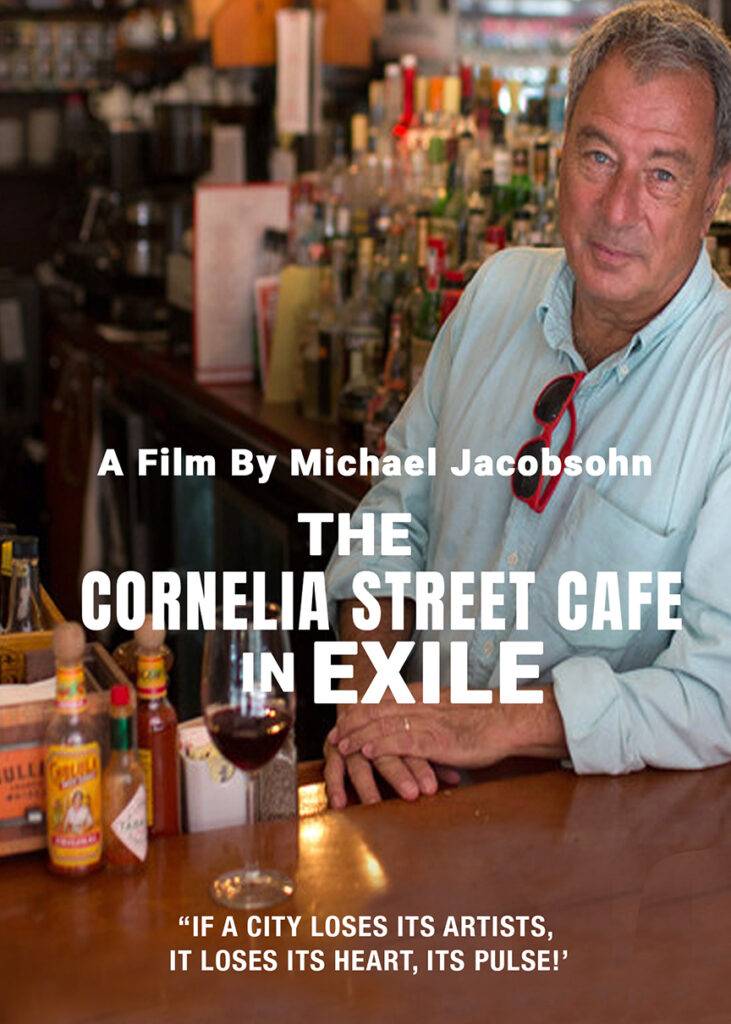

That revelation is one of many unexpected turns in Cornelia Street Café in Exile, directed by Michael Jacobsohn, who has made four feature documentaries, including this one, in 15 years since retiring from a nearly three-decade career as an editor at ABC News. While his other work has focused on “under the grid” artists, Cornelia Street tackles more known entities. It’s a profile of a Village institution and, particularly, the man behind it, that begins at the café’s end and moves forward with rarely a look in the rear view. History is on the menu, but only as an appetizer. The main course is Hirsch: his life after the closure, his Jewish heritage, his abilities on stage, and his attempt to resurrect the café as a nomadic performance series — the Cornelia Street Café-in-exile. Jacobsohn leans hard on talking-head interviews — with Hirsch’s wife and son and performers, among them David Amram, who coined the “in-exile” concept, and Suzanne Vega — as well as abundant show footage. What it definitely is not is a nostalgic dirge for a vanished New York.

The documentary is sly in that way. It nods in the direction of nostalgia but always moves the café story forward rather than wallow in the good old days. Audiences don’t seem to mind — it has been played to sold out crowds at the New Plaza Cinema since it opened in early April. The Star-Revue spoke with Jacobsohn about the film, why he wanted to tell Hirsch’s story, and how it allowed him to explore his own history. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Does your broadcast news experience influence how you make a documentary like Cornelia Street Café in Exile?

I feel like I learned 80%, 90% of my craft as a teenager at the Henry Street Settlement movie club making 16 mm films, and in some ways I discredit what I learned at ABC. So I don’t know, maybe. I would have to think about that.

There’s a lot here that reminds me of a documentary from the 1960s, where it’s people talking to the camera, and clearly talking to you. You’re there guiding it and invisible but not completely.

I think that’s more correct. This film with Robin and the Cornelia Street Café was more challenging than the three other ones I’ve made because Robin is more known. He’s very much loved by a community of artists. The other films are about people who are really under the grid. They’re artists, but nobody knows them, so I had a whole lot more flexibility working with them. If this one seems a little more unruly, the other ones are even more so. Robin lives in Brooklyn, in the brownstone. He has a summer home. He’s a regular family person. So it was more challenging, even though he was generous with the time and very helpful.

It’s clear that there are three or four stories you’re trying to tell. Robin’s story is very big, with a lot of paths that branch off. The broader story about the café is also big and has various break offs. How do you balance that?

My technique is, I run into a character, whether it’s Robin or some of the other people, and I want to go with them through a journey. My thing is usually to follow a person and see what they do. The journey with Robin was, what does a guy do when his life is totally put upside down? When I heard the café was closing, I filmed the last day or two, then I was there when the material was auctioned and the place was destroyed. I also went about interviewing about 30 people. Normally, I don’t do that. I like to observe the person as they go on, not so much go back in time.

But part of the reason I wanted make the film about Robin is because Robin’s background is similar to mine. Robin is nine years older than me, but his parents fled Berlin. My mother fled Berlin to Palestine. My father went to Holland to Palestine. So there’s this connection to the Holocaust and the connection to Germany. I’ve never dealt with it in my own life, so one of the things I was thinking throughout the process was I was partially telling my story through Robert. I’m invisible. I’m shy. I don’t want to be in front of the camera. So using him, I was telling my story.

When you heard the café was closing, is that when you knew there was a film here?

I had been involved with Robin in the café. I knew him off and on, even though I didn’t fully understand the connection between our families, for about 20, 25 years. For the last year of the café, he let me hold monthly screenings in the space, to bring independent filmmakers on Saturday afternoon to have their films shown. So when the café closed, I was thinking, “Maybe this could be an opportunity.” And especially when I heard that everything was going to be auctioned and that he was going to be forced to basically destroy the place, selfishly I’m saying, “This is going to be a real visual thing. Let me capture that scene,” because maybe that’s where the audience would get the sense of the pain of the loss. That was the springboard.

The other thing that he did in the interview that I did the same day that the place was destroyed, was — I asked him how he felt, this and that, and I was kind of surprised that after 41 years, he was really hurt. He compared it to what his parents had gone through in Germany. I always have a distance with all the films I make, you know. I didn’t feel the exact pain that he was going through. I’ve always felt guilty a little about having that distance, you know, that I’m, in a sense, taking advantage of the situation.

There’s a moment in that sequence of the café being gutted where you cut to a junk lugger smashing a cabinet with a really forceful kick. It’s really shocking and brings home just how violent this eviction is.

That’s why he kind of compared it to what his parents experienced. I understood what his parents had suffered when they were forced to leave Germany. That was a moment where I felt that, as a documentarian, I was showing something very graphically and, hopefully, that would trigger within the audience the pain that he was suffering.

You’ve said you wanted this to be more forward looking, but there’s a lot of nostalgia in the film. How do you balance the nostalgia people have for this space and the desire to be more focused on the future?

To a fault, there are many talking heads. That’s hard to sustain. I have that big nostalgia scene where you see Greenwich Village from the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s because I needed something for relief. And I think viewers like that kind of footage, the good old days, you know. David Amram is the one who coined the “café-in-exile” idea, and once I decided to follow that it became, okay, what did that mean? And how did Robin go about moving ahead? Halfway through the film, I realized it’s about all these older people, including me, talking about the good old days, and, you know, moving on to the third act. I wish that Robin can climb Mount Everest and open up something, but I try to be truthful for the situation.

The film’s been selling out at the New Plaza Cinema. What does that mean to you, to see it get that kind of reception?

I’m not so used to having my films in movie theaters and having full houses and then people coming to me and thanking me for doing it, and that it really resonates. As a teenager, when I made 16mm films in the Lower East Side, it was a whole lot easier to get documentaries out. There was a distributor. There were schools renting them. I had screenings at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney. But today, there’s so much content being generated and there are so few theaters, so few distributors. It’s very hard to share documentaries in the theater environment.

I just want to be able to profile somebody. I want to be able to share that person, their inner workings, and to have the audience absorb what the story is and hopefully ask themselves what they think is going on, how would they act. Can they understand what Robin feels? Can they understand what these filmmakers think? Can they go back to when they were younger? I don’t know if this film exactly does that. But I hope when people leave the theater, especially if they’re with another person, that they’ll discuss a little bit what was going on with the film.

Cornelia Street Café in Exile is currently screening at the New Plaza Cinema at Macaulay Honors College, 35 W. 67th Street, in Manhattan. Visit newplazacinema.org for information and showtimes.