When the City of Yes—a voluminous 1,386 page set of zoning text amendments—was approved by the City Council 31-20 in December, all but one of the 20 dissenting votes against the proposal came from council members from the outer boroughs. They voiced fears the Mayoral initiative, which was marketed as an affordable housing proposal, would unleash unchecked development and kill their neighborhoods, especially in communities filled with one- and two-family homes.

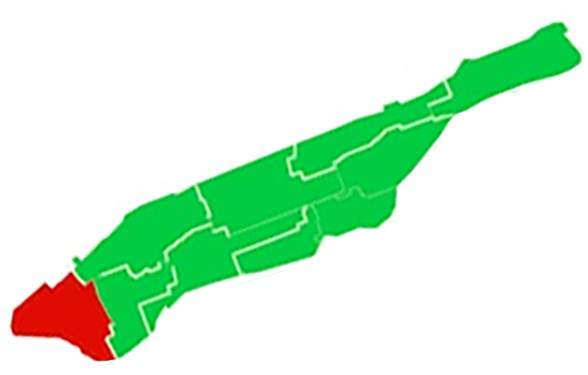

Manhattan Council Member Christopher Marte was the only Manhattan Council Member to vote no on City of Yes. Marte represents Manhattan’s District 1, including much of the Lower East Side, as well as Chinatown, SoHo, and Tribeca.

We wanted to know the reasoning behind his vote and spoke to him in December (this interview has been edited for length).

Village Star-Revue:Why don’t we just start with the reasons you voted no.

Chris Marte: I saw the proposal as a giveaway to real estate developers. That’s not why I became a Council member.

I became a Council member because I wanted to fight against displacement. I wanted to fight against gentrification. I want to make sure people who live in our community can continue to live here and people who are raised here can find an affordable place to live. I felt like City of Yes did not achieve either of those things.

I believe we’re at an affordability crisis. And for a citywide rezoning measure not to mandate affordability, it’s a shame.

When you look at our unhoused population, people living in overpopulated shelters, these are the people trying to look for a home.

The City of Yes supplies only market rate development. It gives developers the option of including affordable housing, “voluntary inclusionary housing” (VIH). What we’ve seen is, when you give VIH, this option, to developers, they don’t take it. Affordability is not a profit-generating metric. It doesn’t serve their shareholders and investors.

Of course, there are some things I agree with in City of Yes, like in “town centers” allowing one story commercial buildings to build to three stories, with added residential housing. But eliminating mandated affordable housing? No, I’m sorry.

And yet, there are so many people who have been persuaded that trickle-down works, that if you build more housing of any kind that it will ultimately promote affordability. What do you say to those people?

You know supply and demand works for oranges, for commodities. If there’s a crisis in the orange market, there’s not going to be a lot of supply, so the demand for it is going to go up.

But when we’re talking about one of the most complex real estate markets in the world where developers have the upper hand, where they hire the most expensive lobbyists to influence legislation, where they create million dollar PACs to elect politicians to do their bidding, when they have lawyers that can kick out any tenant, whether it’s a legal or illegal situation—they run the board game of Monopoly in New York City. Why are we allowing developers to have a massive say on the powers that we have as a Council?

I don’t believe in trickle-down economics when it comes to the real estate market. It just doesn’t work.

We’ve been developing a lot in my district. When you’re on the FDR and you’re looking at Queens, I remember even 15 years ago, the only skyscraper you saw was the Citibank building. Now you can barely see it because there’s so many hi-rise towers in front of it and it seems like every single week, there’s a new building going up.

What we see—not only my district but in Long Island City and Greenpoint, all these areas that have been upzoned drastically—housing prices just continue to rise. The affordable housing that’s there is typically threatened by speculation and shark investors, who really go after low-income communities to try to take over their properties. So trickle-down economics for real estate in

New York does not work and whoever is telling you otherwise is either highly confused or representing their own special interests.

Yet you look at the mainstream media and the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) has done an apparently fabulous job because the City of Yes gets packaged as an affordable housing proposal. How do we move from propaganda to facts?

I think what we’re doing today, this interview, is important, right? Writing about the other side of the story.

One thing that I realized through the City of Yes proposal is that there are organizers in all these communities around the city that believe in the same philosophy I believe in—that we shouldn’t allow the real estate developers to control what happens in New York City, who gets to live here. And I think what we need to do is build a city-wide coalition to really push back.

And so, I am optimistic. You know, when I sat through hours of that hearing—I think other than the chair, I was the person sitting in that chamber longest—something really clicked in me.

Whether you live in the northern Bronx, whether you live or Manhattan, whether you live in, in eastern Queens, there’s people that understand what’s happening in New York. But we don’t have

a structure to really organize all these communities to push back. And so, I think that’s what we have to do. It’s going to be a hard road, right?

Next year’s primary is going to be an interesting one. You know, who becomes our Mayor? And how real estate supports certain candidates and whether those who don’t get that support can win. But we have shown that they can win. REBNY spent tens of thousands of dollars against me. And we were able to organize and educate our communities to show them the reality of the situation.

Would you lay out some of the top flaws in in the City of Yes proposal besides the lack of an affordable housing mandate?

I want to talk about something specific to my district. Chinatown and the Lower East Side have 90 percent of the G districts in the city.

G districts are light manufacturing districts. When you walk around East Broadway and Division Street, you see warehouses. When you go to the second and third floors, there is light manufacturing and there are still some factories operating there. G districts were a way to preserve the kind of light manufacturing that has always been in Chinatown and continues to be, though maybe not at the scale that it once was.

When the city decided to rezone other manufacturing districts, there was a comprehensive plan. The Flower District—there was a huge debate that happened there about how would we build affordable housing. Soho/NoHo, it was a two-and-a-half-year dialogue.

But this administration just eliminated that G district designation. And so we have a lot of these buildings where their property values have skyrocketed overnight.

And what we’re going to see is market rate and luxury condos replace a lot of these commercial buildings and warehouses in Lower Manhattan and none of it’s going to be affordable.

I asked the Mayor, I said “Look, if you want to talk about the G districts, let’s find a way where we could preserve the light manufacturing, but either build housing above it or in certain cases allow for conversion of light manufacturing to residential where we can trigger some sort of affordability metric.” And the administration did not even want to have that conversation.

This is something so specific. City of Yes was more than a thousand three hundred pages long. And so there are these little specific things that might not make the news. But there’s going to be a lot of communities that are going to be drastically changed overnight because of what was hidden in the weeds.

Were there improvements you were able to make to the proposal?

Yes, we were able to limit some of the worst aspects. When the measure first came to the public, the city wanted to do infill [build on open space] in New York City Housing Authority public housing. We successfully organized and pushed back on that and they took that out.

One of the biggest fears that I have is that if you start allowing market rate development in public housing, public housing residents are eventually going to be kicked out and so, I think this was a huge win for the preservation of public housing on public land.

Are there things the city could have changed that would have switched your vote?You know, it’s really hard when you’re trying to do a one-size-fits-all proposal for the whole city.

I really wanted this administration to look back at Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) and make it better, right? (Editor’s note: MIH, a tool of the de Blasio administration, gave breaks to developers, in return requiring they build a percentage of “affordable” units. Critics contended that those units were priced far out of reach of working-class New Yorkers.)

I wanted to say, “Look, we have something that is really one of the only instruments that we have to build affordable housing. Let’s make it better.” Let’s make it affordable for everyday New Yorkers. And let’s expand the percentage of affordable housing because we’re giving developers everything that they want, right? We’re giving them more bulk. We’re giving them more height.

We’re giving them tax incentives, right? Give us something in return.

I think typically when you look at community-based rezoning, there’s always a give and take. But I felt like within the text for City of Yes, it was mostly a gift.

What kind of lobbying and by whom did you experience?

Mostly from the administration. You know, at my office we don’t talk to lobbyists. So we don’t get those phone calls to begin with because people know, we don’t pick up.

But we did what we typically do. We educated our community boards. I’m one of the only Council offices that has a full-time land use director, and he went to Community Board 1, Community Board 2, Community Board 3 to make presentations. We did two Town Halls on the City of Yes; we really wanted to make sure that people understood what was happening.

So, you know, probably I didn’t get as much lobbying as other council members did. But the administration did try to, you know, throw out some carrots potentially to go to get my support.

How would you characterize the influence of REBNY on city government?

It’s massive. Whether it’s on the electoral side where they spend a lot of money in supporting candidates who support real estate interests, or when they stop good things from happening.

Like there’s myself and a few other colleagues who want to pass community-based rezoning plans that were created by the community, plans that would add housing but make sure that we add truly affordable housing. And when we try to talk to City Planning, when we try to talk to Housing Preservation and Development, we get “no.” And we understand who is pulling the strings.

What would you like to see happen to promote truly affordable housing?

I do think we need to relook at mandatory inclusionary housing, right? If we want to have a city-wide approach, it’s going to come through there.

And we want to have a more localized approach. We need to support community-based rezoning policies. For example, we have one in District 1 called the Chinatown Working Group, which would rezone the Chinatown area and the Lower East Side area. And it would mandate, not only new affordability, deep affordability, but it would also curtail speculation by actually setting a ceiling on how high these buildings can be.

What’s the status of that plan?

We did have some talks with City Planning. They were distracted by City of Yes. And because they don’t see this as the most pro-radical upzoning plan, profitable for real estate, they have not made it a priority.

What happens next city-wide? And in District 1?

I think my office understands the negative consequences that can come out of this plan. One of the biggest fears that I have is that now that developers and small landlords have the potential to build a little bit higher, build a little bit wider, it threatens a lot of the rent-stabilized buildings that we have in our district.

We already face those pressures. We see buildings get condemned left and right. But now, there’s much more incentive for these landlords not to give care and support to these buildings. My office—and hopefully city agencies—can do the work to make sure that these landlords are not just abandoning their responsibility in the name of profit.

We get dozens of tenants a day that are going through harassment, that don’t have a lease. We go with tenants to housing court to make sure that they have support. And so this just, you know, makes our job harder. But this is what we’re committed to doing.

Do I recall correctly that one of the tweaks to City of Yes was to add new Department of Buildings staff?

That came outside of the City of Yes text amendment.

I honestly think if City of Yes was all that we were just voting for, it would have not have passed. Even pro-development Council members might have an issue with the text. And that should show you that it took the Mayor and the Governor to give us five billion dollars to get 31 votes in the City Council. It’s remarkable and I think if you put it in that context you realize that they really didn’t have the support to move forward with this proposal.

Part of that five billion dollars is intended to go not only to additional staff—City Planning, HPD, Department of Buildings—but some of it’s going to be allocated for actual affordable housing.

For money to build affordable housing and to support home ownership, and also infrastructure, because there’s certain places in our city that only have one sewer line for half a dozen communities.

It just shows they got desperate. I’ve never seen a rezoning before that was able to get five billion dollars out of it.

What’s the oversight with the five billion dollars to make sure it gets used for good?

That’s the question that we’re going to have to ask, right? We have a mayor that constantly cuts budgets of city agencies left and right. That’s what he’s known for the past three years. Libraries—universally loved, $50 million dollars in a $115 billion dollar budget—targeted.

One can go to church on Sunday and offer prayers for next year’s budget, but still, it’s going to have to be the Council that pushes back. We have to hold the line and remind ourselves that that money should be there. We signed an agreement that said this money should be allocated, but everything is up for debate. People forget about the deal and it never happens.

Can you characterize the media coverage of City of Yes?

There’s two ways you can look at it. Some of these newspapers are afloat because of the real estate industry buying ads and donating to their foundations, right? You open up The New York Times and you see full page ads and so you have to know that there is a biased tilt toward the real estate industry. If you count how many pro-development articles they write versus stories about families being kicked out, it’s like 80/20.

But something like City of Yes is really complicated and for reporters that are well intentioned, they might not have the time to investigate. It’s thousands of pages of work and maybe they don’t have a land use expert that they can ask what does this actually mean? How is this going to be visualized? The city makes it complicated.

So you see a lot of articles talking about just the key points the administration provides. The administration gives out a press release and says, we’re going to build 80,000 new apartments. We’re going to build just a little bit everywhere and that’s what you write about because reporters are underpaid and papers are understaffed. And so you give reporters the benefit of the doubt.

That’s why we do our own things. If people want to see a different perspective, they can come to our town halls, they can read our newsletters. And, hopefully that adds a check and balance to this David and Goliath story.

So chances are you’re going to face YIMBY (“Yes In My Backyard” or pro-development) challengers?

Yes, I have two challengers who would have voted “yes” and they’re blatant about how they feel about trickle-down economics, how we need more supply, and how that’s the number one problem that our city faces.

I’m happy to have that debate. I get challenged almost every time I’m up for election so nothing is new, but it helps me educate my community. I’ve been successful because voters understand it’s a pocketbook issue. People’s rents are going up and even though they might not know why, they feel the pain. When I connect that to speculation, when I connect that to the lack of support they receive as tenants, people get it.

What else should our readers know?

Right now, the mayor’s trying to start a charter revision commission that’s focused on the land use process. I believe he’s going to try to take away the powers of the City Council that we have to negotiate on zoning deals. And so if you think the City of Yes was bad, well it’s back.

I think we’re going to need to organize all these communities to vote “no” on his propositions because sometimes the only good things that the Council gets out of rezonings is through negotiation. And the only way we understand that people are not damaging our environment is because now they have to fill out an environmental impact statement.

If the mayor starts to cripple the only processes we have to understand how these developments are going to affect our communities, it’s going to be disastrous for working-class families in New York City.

I really needed this! Very interesting and informative explanation of and viewpoint on this confusing issue!